Histories of Mathematics, Computing, and AI

My research examines how ideas about knowledge, reason, and intelligence have been reshaped by computing from the mid-20th century to the present. I focus especially on efforts to automate proof and reasoning, and on how these efforts redefined both mathematics and the human mind in computational terms. My first book, Making Up Minds, explores attempts to reproduce mathematical intelligence in computers in the postwar United States, while my ongoing work turns to the history of policing and databanks, analyzing how categories like “criminality” were technologically constructed in ways that continue to shape mass incarceration and racial injustice.

I am also interested in the cultural life of artificial intelligence: the metaphors, assumptions, and promises that have attached to AI across decades, from theorem proving to facial recognition to generative models. This includes tracing how technical “solutions” often emerge through redefinitions, exclusions, and assumptions that are later forgotten, but which leave enduring epistemic and political effects. Increasingly, my work asks how ritual, psychology, and even occult theories of mind became entangled with AI, revealing it as a profoundly human—and contested—project.

Academic Publications

Computers have been framed both as a mirror for the human mind and as an irreducible other that humanness is defined against, depending on different historical definitions of "humanness." They can serve both liberation and control because some people's freedom has historically been predicated on controlling others. Historians of computing return again and again to these contradictions, as they often reveal deeper structures. Using twin frameworks of abstraction and embodiment, a reformulation of the old mind-body dichotomy, this anthology examines how social relations are enacted in and through computing.

Edited by Janet Abbate and Stephanie Dick. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2022.

This chapter examines Woody Bledsoe’s early facial recognition algorithms and the “standard head” assumption that underpinned them. In the 1960s, Bledsoe redefined faces as sets of measured distances and recognition as pseudodistance calculations between them. Because head rotation distorted these measurements in photographs, he introduced a “standard head”—an averaged white male head used to “correct” all others. Though he acknowledged the assumption was unjustified, it allowed him to claim the problem had been solved in principle. His algorithm circulated into the New York State Identification and Intelligence System (NYSIIS), shaping one of the first computerized law-enforcement databanks. I argue that this case exemplifies a broader dynamic: computational “solutions” emerge less from resolving problems than from redefining them in machine terms, often through simplifying assumptions that encode exclusionary norms. The “standard head” reveals how racialized logics were naturalized in early recognition systems, with epistemic and political consequences that persist today.

In Just Code: Power, Inequality, and the Political Economy of IT eds. Jeffrey Yost and Gerardo Con Diaz. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2025.

This article explores the life and work of Chinese American logician Hao Wang. Wang worked at a set of intersections: between Eastern Marxism and Western analytic philosophy; between mathematics and computing; between center and periphery. Though an analytic philosopher himself, Wang became dissatisfied with the field, proposing that it traffics in “fictions” and “abstractions” that neither adequately described nor practically served the realities of human life. In the 1950s, he argued against the imagined universality and rule-boundedness of human reasoning, a central “fiction” of both logic and early artificial intelligence research. Wang drew from Marxism and materialism to argue instead that each person in fact reasons differently, according to the “history of [their] mind and body.” He turned to modern digital computers in hopes that they might create new practical uses for philosophical ideas, and because he believed their difference from human minds was epistemically powerful.

In Osiris, Vol. 38: Beyond Code and Craft, 2023.

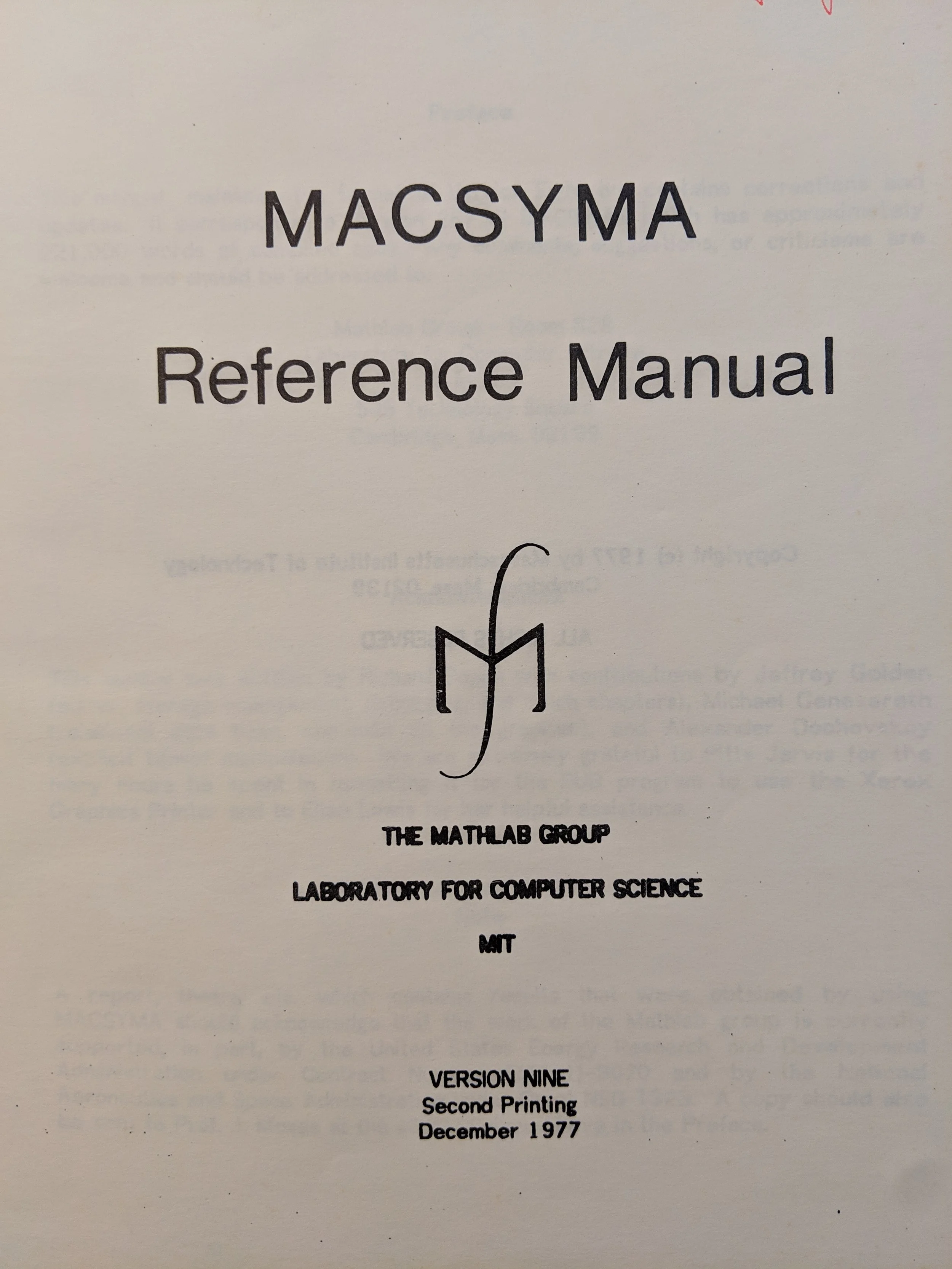

This chapter explores narratives that informed two influential attempts to automate and consolidate mathematics in large computing systems during the second half of the twentieth century – the QED system and the MACSYMA system. These narratives were both political (aligning the automation of mathematics with certain cultural values) and epistemic (each laid out a vision of what mathematics entailed such that it could and should be automated). These narratives united political and epistemic considerations especially with regards to representation: how will mathematical objects and procedures be translated into computer languages and operations and encoded in memory? How much freedom or conformity will be required of those who use and build these systems? MACSYMA and QED represented opposite approaches to these questions: preserving pluralism with a heterogeneous modular design vs requiring that all mathematics be translated into one shared root logic. The narratives explored here shaped, explained and justified the representational choices made in each system and aligned them with specific political and epistemic projects.

In Narrative Science: Reasoning, Representing, and Knowing Since 1800 eds. Mary S. Morgan, Kim M. Hayek, Dominic J. Berry. Cambridge University Press, 2022.

This article explores an early computer algebra system called MACSYMA – a repository of automated non-numeric mathematical operations developed at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology from the 1960s to the 1980s, to help mathematicians, physicists, engineers and other mathematical scientists solve problems and prove theorems. I examine the extensive paper-based training materials that were produced alongside the system to create its users. Would-be users were told that the system would free them from the drudgery of much mathematical labour. However, this ‘freedom’ could only be won by adapting to a highly disciplined mode of problem solving with a relatively inflexible automated assistant. In creating an automated repository of mathematical knowledge, MACSYMA developers sought to erase its social context. However, looking at the training literature, we see that the social operates everywhere, only recoded. This article uses the paper-based training materials to uncover the codes of conduct – both social and technical – that coordinated between the users, developers and machines that constituted the system.

In British Journal for the History of Science, Themes Vol. 5: Learning By the Book, 2020.

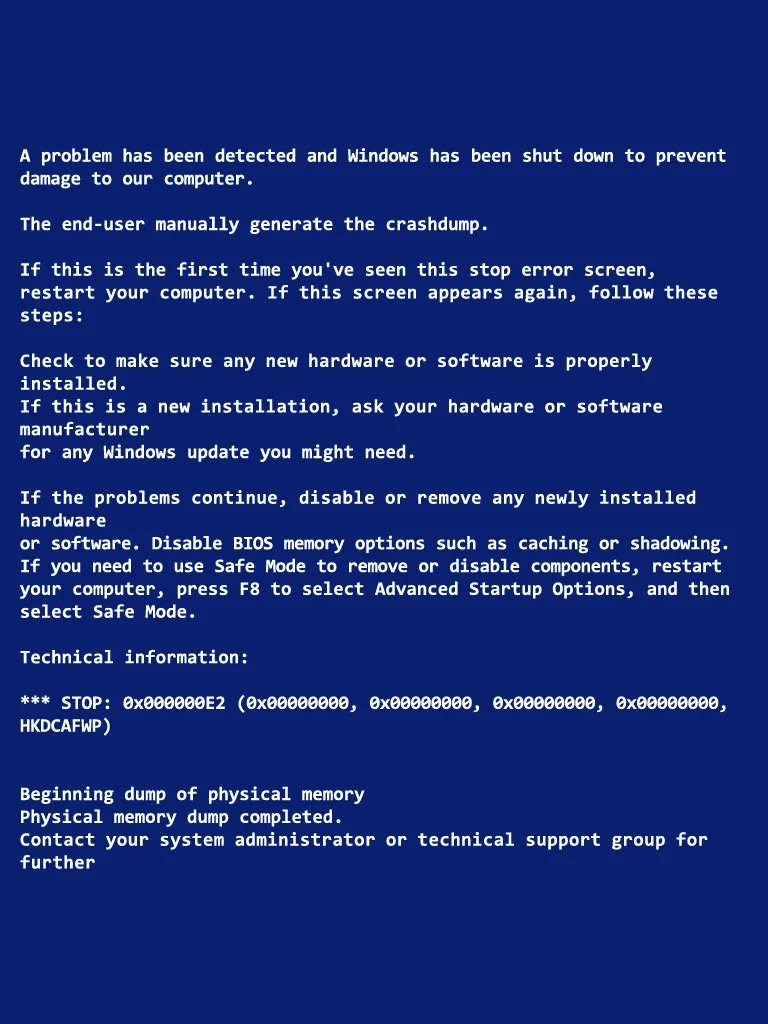

Software is relational. It can only operate in correlation with the other software that enables it, the hardware that runs it, and the communities who make, own, and maintain it. Here, we consider a phenomenon called “DLL hell,” a case in which those relationships broke down, endemic to the Microsoft Windows platform in the mid-to-late 1990s. Software applications often failed because they required specific dynamic-link libraries (DLLs), which other applications may have overwritten with their own preferred versions. We excavate “DLL hell” for insight into the experience of modern computing, especially in the 1990s, and into the history of legacy class software. In producing Windows, Microsoft had to balance a unique and formidable tension between customer expectations and investor demands. Every day, millions of people relied on software that assumed Windows would behave a certain way, even if that behavior happened to be outdated, inconvenient, or just plain broken, leaving Microsoft “on the hook” for the uses or abuses that others made of its platform. But Microsoft was also committed to improving, repairing, and transforming their flagship product. As such, DLL hell was a product of the friction between maintenance and innovation. Microsoft embodied late 20th-century liberalism, seeking simultaneously to accommodate and to discipline various stake holders who had irreconcilable needs. DLL hell reveals the collective work, even when unsuccessful, of developing contractual norms for software as process and practice. Ultimately, many users became disaffected in the face of a perceived failure of technocratic expertise. We attend to implementation, use and misuse, management and mismanagement, in order to recover and reconstruct the complexities of a computing failure.

In IEEE Annals of the History of Computing Vol. 40, No. 4 (2018). Winner of the journal’s Best Paper Award.

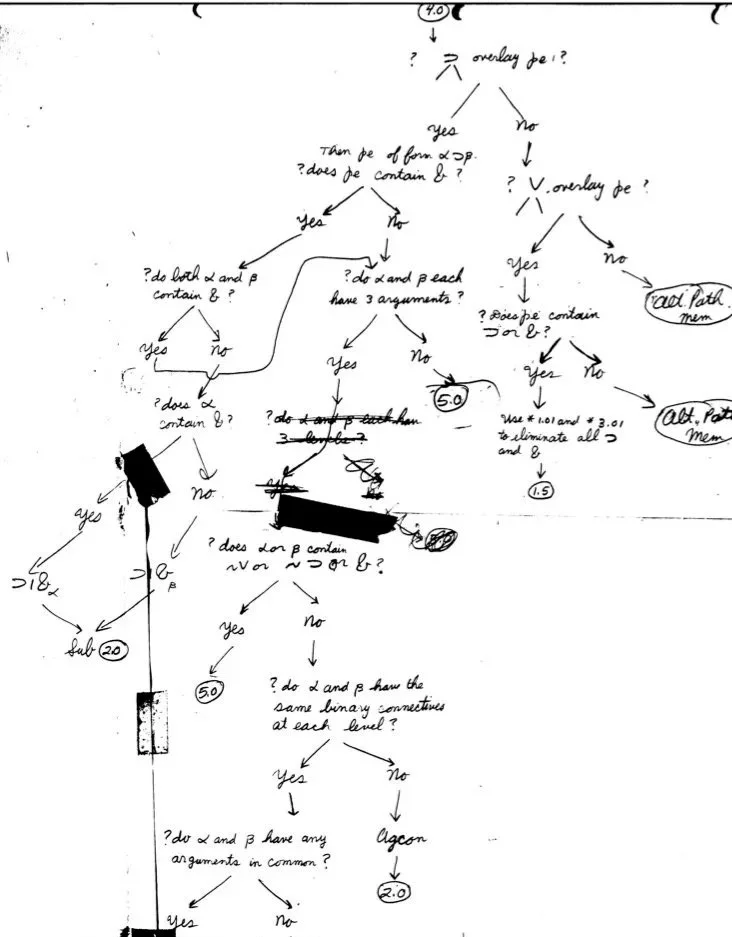

This essay explores the early history of Herbert Simon's principle of bounded rationality in the context of his Artificial Intelligence research in the mid 1950s. It focuses in particular on how Simon and his colleagues at the RAND Corporation translated a model of human reasoning into a computer program, the Logic Theory Machine. They were motivated by a belief that computers and minds were the same kind of thing—namely, information-processing systems. The Logic Theory Machine program was a model of how people solved problems in elementary mathematical logic. However, in making this model actually run on their 1950s computer, the JOHNNIAC, Simon and his colleagues had to navigate many obstacles and material constraints quite foreign to the human experience of logic. They crafted new tools and engaged in new practices that accommodated the affordances of their machine, rather than reflecting the character of human cognition and its bounds. The essay argues that tracking this implementation effort shows that “internal” cognitive practices and “external” tools and materials are not so easily separated as they are in Simon's principle of bounded rationality—the latter often shaping the dynamics of the former.

In Isis, Vol. 106, No. 3 (2015).

During the 1970s and 1980s, a team of Automated Theorem Proving researchers at the Argonne National Laboratory near Chicago developed the Automated Reasoning Assistant, or AURA, to assist human users in the search for mathematical proofs. The resulting hybrid humans+AURA system developed the capacity to make novel contributions to pure mathematics by very untraditional means. This essay traces how these unconventional contributions were made and made possible through negotiations between the humans and the AURA at Argonne and the transformation in mathematical intuition they produced. At play in these negotiations were experimental practices, nonhumans, and nonmathematical modes of knowing. This story invites an earnest engagement between historians of mathematics and scholars in the history of science and science studies interested in experimental practice, material culture, and the roles of nonhumans in knowledge making.

In Isis, Vol. 102, No. 3 (2011).